Content begins here

Contenido de la página principal

Pulsa para colapsar

Without Conflict there is no story

Objectives

In this lesson, we will learn about telling a heritage with comics. In a different way, as with comics, means taking a series of facts and testimonies from the past and making them alive and appealing. Capable of moving and communicating with contemporaries; so as not to get lost in memory and historical archives. For this reason we need to understand and learn the basic dynamics of creative writing, applied to comics.

Without Conflict there is no story

Comics are stories, and stories are an ever living and renewing heritage.

What is conflict

Conflict is a clash between characters, or between a character and the environment. It is not necessarily a physical confrontation, a duel or an armed clash, but is often of an inner, psychological nature that concerns the personality of the character or characters who experience it.

Every story is a conflict

Stories tell of conflicts; even if they are love stories. Every self-respecting story has a character, the protagonist, at the beginning, followed by their difficulties which jeopardise the initial status; even falling in love jeopardises the initial status. Overcoming the difficulties, and the complications that arise, the failures and successes of the protagonist, especially the emotions are the conflict. At the end of the story the protagonist will no longer be the same as before; from being single he/she will have become part of a couple.

Every conflict hides a theme

The canonical stories always tell of a hero slaying a dragon, of the clash between 'Good and Evil'. But what does "Good" and what "Evil" mean? The moment we give a different interpretation to these symbols we are constructing different stories. Or rather we are dealing with a different theme. Let's take an example: Abe is a black man (the hero) in the USA in the 1960s, he needs a raise to pay for the medical care of his sick daughter... Will he get the raise from his white and slightly racist boss (the dragon)?

Build a context by doing research

The theme must always be associated with a context, or if you like, the setting in which the protagonist lives. There are many contexts: space; an enchanted kingdom; during the Second World War... A story with a historical context may seem binding compared to an invented one, but history often has partial knowledge of the facts, which gives room for invention. In order for an invented context to be plausible, it needs to have social rules,

customs, invent habits and technologies... History, on the other hand, provides us with ready-made ones. We just have to study them carefully and reconstruct them. Invention lies in the lives of the characters.

The characters

Characters are vehicles of history, partly victims and partly creators of the story. Their desires push them in directions that will lead them to confrontation. Their actions will build the plot. Their emotions will involve the readers.

Inventing characters means inventing personalities, dreams, desires, fears, memories, experiences and so on. One can take a piece from one's own life and transfer it, suitably adapted, into our invented characters. Or we can take inspiration from friends, family, acquaintances.

The final format conditions the story

In a media where space and time sometimes coincide, the format conditions the writing.

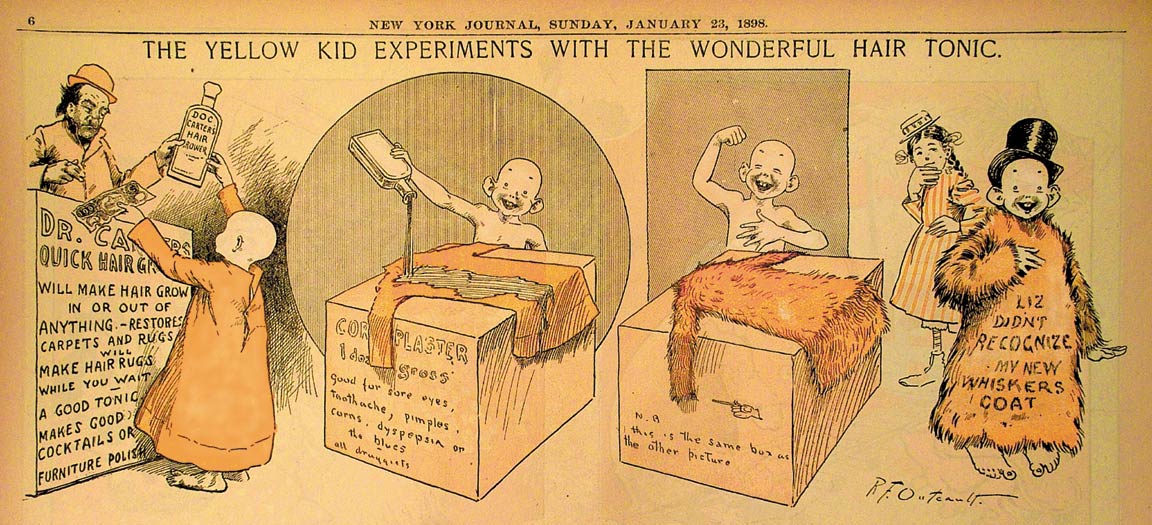

The strip and the vocation for seriality

Comic strips were born in the format of comic strips, which presented small gags and sketches occupying the space of four panels. When it expanded to other genres, the authors discovered a natural vocation of the strip: seriality; that is, the ability to develop stories broken up into many short episodes. In the space of four panels the possibilities of development seem few, but there is a structure that regulates the narrative rhythm of the strip.

Panel 1: Context. Where are we and who is the protagonist?

Panel 2: Goals. What does the protagonist want?

Panel 3: Conflict. Who is his dragon?

Panel 4: Resolution. How is the conflict resolved?

From the Sunday page to the comic book, a new form of seriality

In the evolution of language, the Sunday page, composed of several strips, has widened the possibilities of deepening the story, but seriality has remained part of the media's DNA. Comic books, which presented (and still present today) stories of at least twenty pages, allow more freedom of action, thus creating more complete narrative arcs. The limit of a few pages, however, does not allow for the development of many characters and particularly complex events, so seriality has remained firmly in the media. Characters like Superman or Spiderman have narrative cycles of years, and an editorial life of decades, all broken up into episodes.

The Graphic Novel

The most recent format of the comic book makes it possible to work in a different way, like a novel. There is no page limit, unless the publisher imposes it, and graphic novels generally exceed a hundred pages without problems.

Without the space limits, you can go into the main aspects of the context, go into detail and develop more plots and stories with more characters, and important topics. And also the drawings have more pages to give the reader more complete suggestions.

Arcs or acts don't matter, start from the end

There are universal instruments that support the stories and that are internalised over the years to the point of reinventing them.

The structure in three acts The first to talk about the three-act structure was Aristotle, analysing the Athenian theatre production of his time. Since then it has become a general indication on how to construct an effective story. The first act has a preparatory function, presenting the conflict. The objectives of all characters, primary and secondary. It provides the essential information to start the story and tends to end with a false solution. The second act starts with the definition of the problem and the need to solve it. The character deals with the consequences of the false solution of the first act by laying the groundwork for the resolution that will occur in the third act. The second act ends with a critical situation for the protagonist, momentarily defeated by events. Third act resolves the story and answers all the questions raised in its course and is a closed narrative unit. The character's determination to reassert himself is the trigger for the final act, which rests on a new understanding of himself.

The Hero's Journey

Born out of Joseph Campbell's studies on mythology, the twelve-point structure known as: The Hero's Journey, was made known through the text of Christofer Vogler, a consultant writer at several Hollywood studios. Acting as a practical guide, this outline delves into the characters, defined as "Archetypes" and their potential within the story: the Hero, the Mentor, the Guardian of the Threshold, the Messenger, the Shapeshifter, the Shadow, the Trickster. Thus the Hero, who is the protagonist of the journey, passes through well codified moments:

• The Ordinary World;

• The Call to Adventure;

• The Refusal of the Call;

• The Encounter with the Mentor;

• Crossing the first threshold;

• Trials, Allies, Enemies;

• The Approach to the Deepest Cave;

• The Central Trial;

• The Reward;

• The Way Back;

• The Resurrection;

• The Return with Elixir.

Personal advice: start with the ending

Structures and diagrams are excellent aids, you can use them especially to check the soundness of the story during revision. My advice is to outline the protagonist, his goals and then decide how he will be changed at the end of the story. Basically start with the ending. If we know that our hero will be defeated by the dragon, because the theme of our story will be mad ambition, the beginning and the end will be cardinal in outlining the journey.

A list is better

Finally, it is advisable to write the story in list form rather than in a discursive manner. Everyone builds his or her own method over time, but dividing the moments of the story into portions that will later become chapters, pages, panels, helps to maintain the fragmented view of the media.

Conclusions

Finally, it is advisable to write the story in list form rather than in a discursive manner.

Video and PDF presentationPulsa para colapsar

The following video explains the content of this lesson and shows some examples:

Video T2.L1. How creative writing applied to comics

Here you have the content of the video in pdf in case you need to use it in your classroom:

Lesson contents in PDFPulsa para colapsar

Here you have the contents of the lesson in PDF: